In a recent statement, World Bank President Ajay Banga addressed growing concerns over the Indus Waters Treaty, emphasizing that the agreement cannot be unilaterally suspended or modified without mutual consent from India and Pakistan. The clarification comes at a time of heightened tensions following India’s reported suspension of the treaty and closure of the Attari-Wagah border crossing, prompted by a recent attack in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir.

World Bank’s Limited Role

Speaking in an interview, Banga outlined the World Bank’s role as strictly administrative, rooted in its facilitation of the treaty’s creation in 1960. The Bank manages a trust fund to cover the operational costs of the treaty’s mechanisms, such as the appointment of neutral experts or arbitration courts when disputes arise. “Our role is to ensure the processes outlined in the treaty are followed. We have no authority to make decisions or intervene beyond that,” Banga stated. He further noted that no formal communication regarding recent developments has been received from either nation.

The treaty, a cornerstone of water-sharing between India and Pakistan, allocates control of the eastern rivers—Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas—to India, while Pakistan oversees the western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab. India is permitted to use the western rivers for non-consumptive purposes, such as hydroelectric power, provided projects adhere to strict “run-of-the-river” guidelines to protect Pakistan’s downstream water rights.

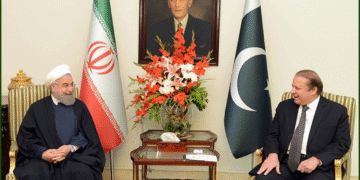

Pakistan’s Firm Stance

Pakistan’s Foreign Office responded to India’s actions with a formal statement, reaffirming the treaty’s status as a binding international agreement. Spokesperson Shafqat Ali Khan emphasized that Pakistan views any violation of the treaty as unacceptable and vowed to defend its rights through international forums. “The Indus Waters Treaty remains fully operational, and both nations are obligated to uphold its provisions,” Khan said.

The statement reflects Pakistan’s reliance on the western rivers, which are critical for its agriculture and economy. Any disruption to water flows could have severe consequences for millions of farmers and communities downstream.

A History of Cooperation and Conflict

The Indus Waters Treaty emerged from the complex partition of British India in 1947, which split the Punjab region’s intricate irrigation network across the newly drawn border. Recognizing the potential for conflict over shared rivers, the World Bank mediated nine years of negotiations, culminating in the treaty’s signing by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani President Ayub Khan.

Despite its success in preventing large-scale water conflicts, the treaty has faced challenges. Disputes over India’s hydroelectric projects on the western rivers, such as the Kishanganga and Ratle dams, have periodically strained relations. The treaty provides mechanisms for resolving such disagreements, including consultations, neutral expert evaluations, or arbitration, but tensions often escalate before resolutions are reached.

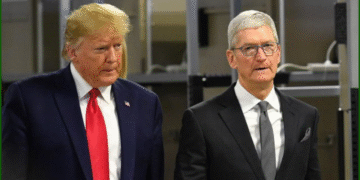

Current Developments and Implications

India’s reported suspension of the treaty and closure of the Attari-Wagah border—a vital trade and cultural link—mark a significant escalation in bilateral tensions. The move follows a deadly attack in Pahalgam, which India attributes to cross-border aggression. However, Banga’s remarks underscore that the treaty’s framework does not permit unilateral suspension. “Any change, whether amendment or replacement, requires both countries to agree,” he reiterated.

For Pakistan, the treaty is not just a legal document but a lifeline for its water-scarce agrarian economy. Analysts warn that prolonged uncertainty could exacerbate distrust and hinder cooperation on other bilateral issues. Meanwhile, India’s actions may reflect domestic pressures to adopt a hardline stance, though they risk complicating its international standing if perceived as violating a long-standing agreement.

The Path Forward

As both nations navigate this latest crisis, the World Bank’s neutral stance highlights the need for dialogue. The treaty’s resilience over six decades demonstrates its value as a model for transboundary water management, but its success depends on the willingness of both parties to engage constructively. For now, the international community watches closely, hoping for de-escalation and a return to diplomacy to safeguard this critical agreement.