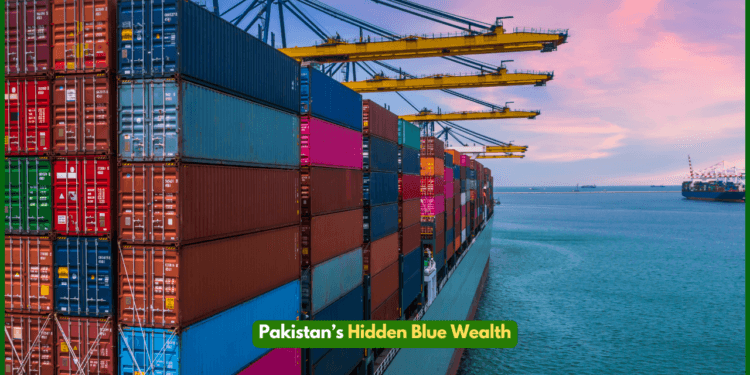

ISLAMABAD – Pakistan’s economy, battered by a stagnant export base and limited diversification, teeters on the edge of a transformative opportunity: its hidden blue wealth. Stretching over 1,000 kilometers along the Arabian Sea and astride vital global trade routes, the nation’s coastline is a goldmine waiting to be tapped. Today Pakistan News dives into how this underutilized maritime sector could catapult Pakistan toward prosperity—if it can overcome steep hurdles.

Currently, the blue economy—encompassing shipping, fisheries, tourism, and renewable energy—contributes a mere 1.5% to 3% to Pakistan’s GDP. Experts project that with strategic planning, this could soar to 10-15% within decades. Shipping alone could rake in $8-10 billion annually by 2030-2035, fisheries and aquaculture another $17-18 billion, and maritime tourism, tidal energy, and Gadani’s ship recycling could push total revenues past $40 billion. “It’s a sleeping giant,” says Karachi-based economist Dr. Fatima Ali. “Pakistan’s maritime edge is criminally overlooked.”

The potential is vast. Gwadar Port, often touted as a China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) linchpin, remains underutilized but could evolve into a regional trade hub under a hub-and-spoke model. Fisheries, despite Pakistan’s rich marine biodiversity, lag due to outdated practices, while coastal tourism—from Karachi’s Clifton Beach to Balochistan’s rugged shores—languishes without investment. Offshore wind and tidal energy, viable along Sindh’s coast, promise green power, yet remain dormant.

So, what’s holding Pakistan back? A litany of challenges: policy gaps, regulatory inefficiencies, crumbling infrastructure, and a stark lack of maritime awareness. Political instability in Balochistan, home to Gwadar, spooks investors, while climate change threatens marine ecosystems—overfishing, pollution, and rising sea levels loom large. “We’re wasting a natural gift,” Ali warns, noting the absence of a cohesive maritime strategy.

To unlock this wealth, bold steps are needed. First, a comprehensive maritime policy must plug gaps, balancing growth with sustainability. “It’s not just about profit—it’s inclusive development,” says Ali. Second, modernizing ports like Gwadar and Karachi is non-negotiable—think deeper berths, faster cargo handling, and transit trade hubs. Third, human capital demands urgent investment: training programs for fisheries, shipbreaking, and coastal entrepreneurship could turn opportunity costs into billions.

Fourth, sustainability is key. Ecosystem-based solutions—like mangrove restoration—and circular economy principles could curb waste and protect marine life, with private firms leading on eco-friendly practices. Fifth, domestic investment in tidal energy, deep-sea fishing, and merchant shipping could spark quick wins. International partnerships—with nations like Norway or Singapore—would bring tech and expertise to the table.

Financing this shift is tricky amid Pakistan’s fiscal crunch, but a Blue Economy Fund (BEF) could be the answer. Modeled on global green funds, the BEF could draw retail and institutional investors, plus World Bank grants, targeting projects like aquaculture ($1 billion potential) and port upgrades. “Start small—coastal energy, fishing—then scale up,” Ali suggests.

The stakes are high. Beyond economics, a thriving blue sector could ease unrest in coastal belts, offering jobs and stability. “It’s a strategic lifeline,” Ali insists. With time ticking, Pakistan must act—or watch its maritime wealth slip away.