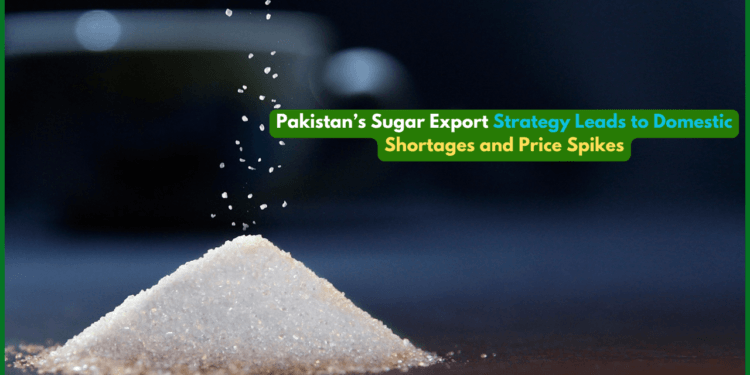

Pakistan’s government sugar export policy, intended to boost the sugar industry’s revenue and stabilize farmer incomes, has backfired, triggering domestic shortages and soaring prices as Ramadan approaches in 2025. Recent data and analyses reveal that the decision to allow exports in 2024/25, driven by surplus production estimates, has strained local supplies, leaving consumers grappling with higher costs and limited availability, according to industry reports and economic studies.

In 2024/25, Pakistan’s sugar production reached 6.8 million tons, a 3% increase from the previous year, as forecasted by agricultural experts. The government, responding to the Pakistan Sugar Mills Association (PSMA) requests, approved exports of up to 500,000 tons in tranches, aiming to capitalize on firm international sugar prices, as noted in a market analysis. However, this move has led to a significant shortfall domestically, with sugar stocks dropping to an estimated 114,000 metric tons—far below the industry’s claim of 1.5 million tons—causing prices to spike to PKR 140–160 per kilogram in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, per a recent economic report.

The policy’s unintended consequences stem from contradictory claims over surplus stocks, as highlighted in a national newspaper. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif deferred a decision on exports in April 2024 due to discrepancies between government estimates and PSMA figures, but the eventual approval in May 2024 exacerbated the crisis. The government’s emphasis on domestic price and supply controls, intended to ensure food security, failed to prevent exports from depleting local reserves, leading to public outcry as Ramadan—a time of heightened sugar demand for sweets and traditional dishes—approaches.

Economic researchers argue that overregulation and lack of competition in Pakistan’s sugar market, as detailed in a policy study, have worsened the situation. The study points to the government’s slow reaction to cancel export permits amid rising local prices, which aggravated the shortage. International sugar prices, while firm, did not offset the domestic fallout, with exports remaining insignificant in volume but devastating in impact, as noted in an agricultural insight report.

Farmers, initially benefiting from export earnings, now face uncertainty as domestic demand outstrips supply, threatening their ability to settle liabilities with sugarcane growers. Meanwhile, consumers are bearing the brunt, with sugar prices rising 20% since late 2024, straining household budgets during a period of economic hardship, including inflation and currency depreciation, as per market analyses.

The policy has also drawn criticism for its political sensitivity, given the involvement of influential families in the sugar industry, which has historically influenced export decisions. Past incidents, such as the export of wheat and sugar followed by imports at higher costs, have fueled skepticism about government oversight, as reported in a national publication.

As Pakistan navigates this crisis, experts recommend stricter monitoring of sugar stocks, improved data transparency, and a balanced approach to exports versus domestic needs to prevent future backfires. The government is under pressure to reconcile figures, stabilize prices, and ensure availability ahead of Eid-ul-Fitr in April 2025, but the damage to consumer trust and market stability may linger.